Duran Duran have something to prove: Vintage ’80s interview

Excerpted from an article by Philip Bashe

Having performed four shows in four nights at London’s cavernous Wembley Arena, Duran Duran lead singer/ sex symbol Simon Le Bon has begged off interviews in order to conserve what’s left of his rapidly deteriorating voice.

No doubt female readers will be disappointed, but Le Bon will soon be taking himself out of circulation anyway, having recently announced his engagement to Claire Stansfield, a Canadian model and photography student.

In Le Bon’s place are keyboardist Nick Rhodes and bassist John Taylor, who, although they may not enjoy Simon’s heartthrob status, are the heart and soul of the band they founded in 1978. Duran are highly departmentalized, and there’s no bandleader as such, but Rhodes, at 21 the youngest member, comes closest.

For the group’s third album, Seven and the Ragged Tiger (Capitol), he remained sequestered in the studio with producers Alex Sadkin and Ian Little long after the others had returned to their residences on the Caribbean island of Montserrat.

“I refuse to leave until the last part of anything is done,” he says. “For me, the studio is my playground.” Rhodes’s soft features and his slight stature belie his powerful ambition. He’s the intense one. While the others pose for publicity photos chipperly, as if merely modeling haberdashery, Rhodes’s fixed stare seems to pierce the camera lens.

It’s not surprising, then, that he takes the most umbrage at the criticisms leveled at Duran Duran, especially at home in England, where their image as self-styled bons vivants is often condemned as irresponsible and, worse, irrelevant.

“Our pretty friends contrive to cash in on their profitable pose,” sniffed one typically derisive British magazine. “Certain segments of the music press may think that our image is more important than our music, but we’ve always stated that the music comes first,” counters Rhodes, running a hand through his thatch of flaming orange hair.

“But we do believe in presenting ourselves properly. Personally, I prefer seeing somebody dressed up for an occasion, as if going out for a meal at a top restaurant.

“I’ll also go to McDonald’s in jeans and a T-shirt, but for our videos and photos, yes, there is a certain amount of extravagance. It’s an honest representation. And to be slighted by criticisms like ‘They’re a bunch of clothes horses,’ it becomes a bit irritating.”

Except for guitarist Andy Taylor, a Geordie from Newcastle, Duran Duran’s members hail from Birmingham, an industrial city where fashion is not nearly as high a priority as finding a job and feeding the family.

“It’s basically working class,” says drummer Roger Taylor, 23. “My dad used to work in a factory.”

“That’s what everybody used to do,” adds John Taylor, also 23.

Nick Rhodes, born into this setting as Nicholas James Bates, was always style-conscious. Dressing up was a means of escaping the environment without leaving the city limits, for who could afford to?

It is Rhodes’s contention that Duran Duran fulfill a similar purpose, offering their audience liberation through music, although he prefers to call it entertainment, not escapism.

“Certainly we all have political views,” he says resolutely, in reference to claims that the band lacks substance, “but I don’t feel we have to preach them and ram them down people’s throats in all our songs. We’re fully aware of the problems everyone has at the moment.”

“Just because it’s not screaming in agony,” adds John Taylor, “doesn’t mean it’s not a statement.”

Both Taylor and Rhodes feel that Seven and the Ragged Tiger will be the album to change people’s minds about Duran Duran and about what John calls their “disposable im-age.” “It has more musical substance,” declares Rhodes, “simply because we’re more professional; we’re more capable musicians.”

The new LP is the most dance-oriented record the band has made yet—”the blackest a white band’s ever got,” John Taylor says in half-jest.

Though the music does retain a relativity to Duran Duran (1981) and Rio (1982), songs like “Union of the Snake” and “The Reflex”—both dance tracks hammered together by Roger’s bass drum pedal and John’s jagged bass lines—would have sounded out of context on those albums. Exactly the point, says Rhodes.

“We felt that we didn’t take a large enough step away from the first LP with Rio. It was too timid, although it did work very well for us. With your third album, it’s easy to get stuck in a rut, which we had no intention of doing. We wanted to still be identifiable as Duran Duran, but we wanted to stretch our parameters.”

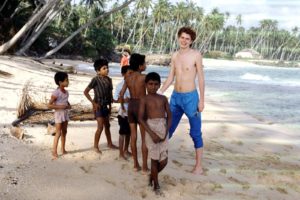

The band is quite pleased with the end-product, but the time spent making the record in Montserrat was fraught with problems. Constant harassment from fans and the press made recording at home an impossibility, so Duran decided to go to Montserrat, “to get away from everybody,” says Rhodes.

“We thought it’d be great, it’d be quiet, and we’d be able to get a lot of work done. “But, of course, when we got there, there was blistering heat every day. You’d be too hot outside, then you’d go inside and freeze to death from the air-conditioning. It was like culture shock, like going from China to New York.” (Continued on page below)